Sometimes geographical constraints necessitated unsympathetic traffic routes, as evidenced by this section of the GSP running through a cemetery in East Orange

GSP planners had to figure out how to integrate the GSP with existing roads, buildings, and natural features. This photo is of the Cape May terminus in 1955

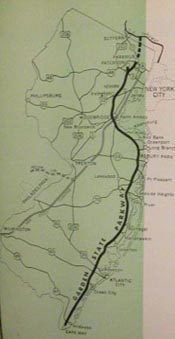

The task of planning the construction of a brand new 173-mile road through one of the most densely populated states in the nation was not simple. The project required feasibility studies, skilled and dedicated leaders, large infusions of cash, a team of qualified consultants, and a highly effective public relations campaign to build political and broad popular support. A well planned project could change the course of New Jersey history; a poorly planned project could take decades to build—or worse, fail to win the public support needed to fund it.

The Garden State Parkway was hailed as “the road of tomorrow” by politicians, planners, and engineers. It would be the safest, most efficient, and beautiful road of its day, combining the conveniences of the modern superhighway with the scenic beauty of New Jersey

The GSP was the dream of Governor Walter Edge and his Secretary of Highways Harold Griffin. The pair began the project in 1946 using state funds to cover initial costs. However, the project languished from a lack of money, and only 4 miles were constructed between 1946 and 1950.

In 1952, the New Jersey Legislature created the New Jersey Highway Authority (NJHA) to oversee the project and secure its financing. Within weeks of the final approval of the legislation, the Commissioners worked to determine the best alignment, arrange for necessary funding, and begin design of the massive roadway. The effort paid off, with planning and construction of the main stem between Paterson and Cape May completed by early 1955.

"I never see just a road from this window; I see people…businessmen, fathers, mothers, children- all going someplace, all wanting to get there quickly, all deserving to get there pleasantly and safely."

- Former NJHA Executive

Director Louis Tonti, 1964.

The Commissioners hold an information packet entitled “What the Garden State Parkway Means to You.”

Date unknown.

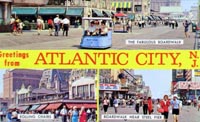

To many in the political and business communities, the need for the GSP was indisputable. In the north, commuters sat idling on local roads day in and day out as the population growth of the urban areas outpaced road construction. Trucks and other commercial vehicles competed with passenger cars for space on the road and made a bad situation worse. In the south, traffic clogged the network of local roads that carried visitors to the Shore throughout the summer tourist season. Resort towns like Atlantic City and Cape May faced stagnation if officials could not devise a way to get people there faster and safer.

The State of New Jersey started to address the problem in 1946 when construction of the Route 4 Parkway began in Bergen County. However, construction was slow and costly, and at the pace it was moving, it seemed likely that the road would never be finished.

In 1952, Governor Alfred Driscoll proposed that a new agency with the power to issue bonds assume control of the project and oversee ongoing work on the GSP until its completion. Although the idea itself was sound, numerous challenges still lay ahead.

The greatest challenge facing the GSP in the early years was financing. The GSP concept was supported by numerous feasibility studies that advocated for toll collection and independent management. However, it was a risky proposition, and the price tag seemed extremely high. To get the project accomplished quickly, the Authority would need a large infusion of cash in a short period of time, and they would need the State’s support to secure the necessary funding.

The political atmosphere was difficult and Governor Alfred Driscoll campaigned widely across the state for passage of the referendum. In the Summer of 1952, the Governor appeared in a short film that hailed the GSP as the solution to traffic congestion, with the promise that dads would have the chance to vacation with their families at the Shore without having to spend the entire weekend stuck in traffic on U.S. Route 9. Expanding on this message, informational packets were distributed upon request in order to show how the GSP would benefit these families.

In 1954, the 116-mile trip from Paterson to Atlantic City on the GSP was estimated to take 2.6 hours and cost $1.75 in tolls, an average of 1.5¢ per mile. The same trip via local roads was estimated to take 3.7 hours. The same trip today costs $2.10, or 1.8¢ per mile, but tolls are only paid in one direction.

Atlantic City was a favorite vacation spot for working class families in the 1950s.

The Atlantic City interchange, 1965.

The Shore had long been one of New Jersey’s greatest recreational assets and drew millions of visitors every summer. The boardwalks in Atlantic City and Ocean City and the Victorian-era houses of Cape May were popular destinations for tourists from across the Mid-Atlantic, yet the problem lay in getting there. U.S. Route 9 was the most direct north-south route along the Shore, but it passed directly through many towns and villages causing repeated delays. The NJHA estimated that in 1954 it took 3.2 hours to drive from Newark to Atlantic City on existing roads. A movie produced by the NJHA in 1952 to encourage voters to approve the bond referendum showed moms and their kids frolicking in the ocean while dads sat in traffic on their way to meet them for their summer vacation.

GSP planners were acutely aware of the need for the road and the impact it would have on these communities. One of the first Authority Commissioners was Bayard L. England, President of Atlantic City Electric Company, who clearly foresaw the economic benefits inherent in making Atlantic City and other Shore towns more accessible to a wider public.

"It [Route 4 Parkway] was like building a house by buying the cinder blocks for the foundation and then waiting to save more money for some lumber."

- Former NJHA Executive

Director Louis Tonti,

1964.

The Essex County section featured low-sprung, stone-faced bridges and wide grassy medians.

The State Highway Department built and maintained several sections prior to 1952, including 13 miles in Union and Middlesex counties.

The New Jersey State Highway Department began the Parkway Project in 1946. Using state funds, four short sections of road were built in Essex, Union, Middlesex, Ocean, and Cape May counties between 1946 and 1953.

The Highway Department was entirely dependent on the New Jersey Legislature for its capital and maintenance budgets. However, the Parkway project never received the proper financing it needed for design, property acquisition, and construction. Consequently, progress was slow and frustrating. In addition, the state was legally prohibited from collecting tolls on these sections of the road because they had been financed by state revenues, and to do so, would result in double taxation. On the other hand, if the project were to have continued under its original arrangement, the entire 173-mile GSP would have had to depend upon taxpayer funds for maintenance and expansion.

When the NJHA assumed control of the Parkway in 1952, the four existing sections remained toll free. Motorists could travel unfettered on a 6-mile stretch in Essex County, for 13 miles between Union and Woodbridge, 3 miles around Toms River, and a 4-mile bypass around Cape May Court House. The NJHA warned that allowing these areas to remain toll-free would have long term implications on revenue and traffic. The Authority’s General Engineering Consultants conducted a traffic survey in 1958 and predicted that the Parkway faced deficit operations by 1964 unless measures were taken to control the increasing load of toll-free vehicles using the Essex County section. The report maintained that the congestion generated by the free riders would discourage paying motorists from using the northern areas with the result that the GSP could not realize the increased income it would need to meet all future obligations.

The barrier toll plazas were designed, in part, to address this problem by creating toll collection areas at various points regardless of entrance or exit points. In absence of these toll plazas, drivers who entered the Parkway on a toll section had the advantage of exiting via one of the numerous free-section exits without having to pay a cent.

Katharine E. White served as Chairwoman of the NJHA from 1955-1964. White was the daughter of a U.S.

Diplomat and served three terms as Mayor of Red Bank, before becoming the first woman to head a state

transportation authority. She was appointed Ambassador to

Denmark by President

Johnson in 1964

A meeting of the NJHA Board of Commissioners, 1958.

The new NJHA Administration Building in Woodbridge, c.1964.

The GSP was constructed and managed by the New Jersey Highway Authority, an agency created in 1952 to oversee large-scale transportation projects across the state. Governor Alfred E. Driscoll signed the New Jersey Highway Authority Act into law on April 14, 1952 to finance and oversee construction of the GSP and other highway projects throughout the state. The legislation passed by both the State Assembly and Senate gave the Authority to “acquire, construct, maintain, repair, and operate ‘highway projects.’” The Act specifically authorized the construction of the GSP, but also envisioned the Authority overseeing other large-scale transportation projects throughout the state; the 173-mile GSP was the only project undertaken and managed by the Authority. Other long distance roads were constructed and managed by individual authorities, such as the South Jersey Transportation Authority, created in 1964 to construct the Atlantic City Expressway. In 2003, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and the New Jersey Highway Authority were merged and the Turnpike Authority assumed responsibility for the maintenance and operation of the GSP.

D. Louis Tonti was hired as the Executive Director upon the retirement of Ransford Abbott in late 1954

Katharine E. White, Governor Meyner, Orrie de Nooyer, and Bayard L. England, 1956.

Commissioners Sylvester C. Smith and John Townsend, 1958.

NJTA Commissioners (L-R) Bayard L. England, Orrie De Nooyer, and Ransford J. Abbott, 1954.

Critical to the success of the GSP was the selection of competent and experienced NJHA Commissioners to make decisions and set policy and a committed Executive Director who could implement those decisions and get the GSP built. The NJHA was managed by a Board of three commissioners appointed by the Governor and approved by the Senate. Each Commissioner shared in the leadership of the Board, with one person serving as Chair, another as Vice Chair, and the third as Secretary/Treasurer. Commissioners served 9-year terms, with the original three members serving staggered terms of 3, 6, and 9 years.

The Commissioners most directly linked with the construction and early years of the GSP:

Ransford J. Abbott of Red Bank, State Highway Commissioner from 1950 to 1954, was appointed to the Authority June 26, 1952 by Governor Alfred E. Driscoll and designated as its first Chairman. He resigned early in 1954 to assume the post of Executive Director, for which he served the Authority for the remainder of the year. Mr. Abbott died in 1956.

Bayard L. England of Linwood, President of Atlantic City Electric Company, was appointed to the Authority for a 6-year term on June 26, 1952 by Governor Driscoll and designated as its first Vice Chairman. He was elected Treasurer at the July 2, 1952 organization meeting. In May 1954, he was re-designated as Vice Chairman by Governor Meyner to succeed Ransford J. Abbott and took the oath of office on June 1, 1954. His term as an Authority member expired on June 26, 1958.

Orrie de Nooyer of Garfield, Vice President for Purchasing for Julius Forstmann & Company, was appointed to the Authority for a 3-year term on June 26, 1952 by Governor Driscoll. He was elected Secretary at the July 2, 1952 organization meeting. In May, 1954, he was named Chairman by Governor Meyner to succeed Ransford J. Abbott and took the oath of office June 1, 1954. His term as an Authority member expired on June 26, 1955.

Katharine E. White of Red Bank, three-time Mayor of Red Bank between 1950 and 1956, was appointed to the Authority by Governor Meyner early in 1954 to complete the 9-year term of Ransford J. Abbott. She took the oath of office April 7, 1954, and was elected Secretary at the June 15, 1954 reorganization meeting. On March 8, 1955, she was named Vice Chairman by Governor Meyner to succeed Bayard L. England and was elected Treasurer the next day. On August 30, 1955, she was named Chairman by Governor Meyner to succeed Orrie de Nooyer and relinquished her elected position.

Dr. John B. Townsend of Ocean City, a practicing physician, was appointed to the Authority by Governor Meyner in March 1955, to complete the 6-year term of Bayard L. England. He was elected Secretary at the March 9, 1955 reorganization meeting. On August 30, 1955, he was named Vice Chairman by Governor Meyner upon Commissioner White’s elevation to the chairmanship. He was reappointed for a 9-year term as a member of the Authority by Governor Meyner in 1958. He resigned as Secretary on August 17, 1959.

Sylvester C. Smith Jr. of West Orange, General Counsel of the Prudential Insurance Company of America, was appointed to the Authority by Governor Meyner in August, 1955, for a 9-year term to succeed Orrie de Nooyer. He was elected Treasurer at the September 1, 1955 reorganization meeting.

Reprinted from “The First Five Years of the Garden State Parkway, 1954-1959” (1959)

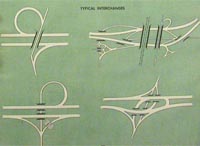

Configuring the GSP for interchanges, service areas, and toll plazas required an understanding of both local and visitor needs.

View of the GSP showing the integration of a modern superhighway in a picturesque, landscaped setting. Date and location unknown.

The GSP was designed to provide motorists with the best of both worlds: the speed and convenience of a modern superhighway combined with the beauty and relaxing experience of a country road. Engineers and landscape architects worked together to create a road that was both safe and enjoyable and incorporated many new and innovative design elements into the final plans. The result was a roadway with two travel lanes in each direction separated by a wide median filled with native plants and trees, gentle slopes and curves, moss-colored bridges that blended into the landscape, “singing shoulders” (also called rumble strips), numerous toll plazas, and unique signage.

The final design of the GSP was the product of a significant collaboration between engineers, landscape architects, and various traffic and financial consultants. Leading the design team for many years was Chief Engineer Harold Griffin. Griffin was “loaned” to NJHA from the State Highway Department (now the Department of Transportation) in 1952 and collaborated with engineers from Parsons, Brinkerhoff, Quade, & Douglas (general engineering) and Coverdale & Colpitts (traffic engineering) to develop a plan that was both functional and beautiful. Gilmore Clarke, a landscape architect from New York who was famous for his designs of the Bronx River, Palisades Interstate, and Henry Hudson parkways and for his work on the 1939 Worlds Fair, also consulted on the design of the GSP. Harold Griffin is credited with inventing the traffic circle, the reflective curb, and “singing shoulder.” He retired shortly after the GSP was finished, but came out of retirement to design the Atlantic City Expressway (opened in 1964) and served as the managing authority’s first Executive Director.

The Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge, completed in May 1956, was the last major construction project along the main stem

This diagram published in the 1952 NJHA Annual report shows the four basic configurations for GSP interchanges.

The Garden State Parkway was designed to be one of the safest, most appealing, and innovative roads ever constructed. However, designing such a road through New Jersey presented an array of challenges, owing to its diversity of topography, population, economies, and needs. In the north, the GSP needed to serve as a commuter highway, enabling workers in the areas around Newark to move quickly and easily to and from work. In the south, the GSP was to be the primary conduit to the Jersey Shore, carrying vacationers to the resort communities that dotted the coastline. Most importantly, it needed to achieve both of these goals safely.

To meet the needs of all motorists who might use the GSP, while creating a single, unified roadway, Chief Engineer Harold Griffin and his design consultants incorporated several consistent design elements along the GSP’s entire alignment.

Low-sprung, masonry bridge detail.

High concrete and steel bridges carried the GSP over existing roadways and created new interchanges like this one near Paterson.

Reinforced concrete and steel girder bridge under construction at the Seaville Interchange, 1954.

Detail of banded, reinforced concrete bridge with steel span and girder. Location unknown.

The Garden State Parkway was designed to be one of the safest, most appealing, and innovative roads ever constructed. However, designing such a road through New Jersey presented an array of challenges, owning to its diversity of topography, population, economies, and needs. In the north, the GSP needed to serve as a commuter highway, enabling workers in the areas around Newark to move quickly and easily to and from work. In the south, the GSP was to be the primary conduit to the Jersey Shore, carrying vacationers to the resort communities that dotted the coastline. Most importantly, it needed to achieve both of these goals safely.

To meet the needs of all motorists who might use the GSP, while creating a single, unified roadway, Chief Engineer Harold Griffin and his design consultants incorporated several consistent design elements along the GSP's entire alignment. In the north, the GSP needed to serve as a commuter highway, enabling workers in the areas around Newark to move quickly and easily to and from work. In the south, the GSP was to be the primary conduit to the Jersey Shore, carrying vacationers to the resort communities that dotted the coastline. Most importantly, it needed to achieve both of these goals safely.

Detail of a submerged median, milepost and date unknown.

Detail of an artificial berm, Milepost 169.4, northbound, October 1972.

Research of the Pennsylvania Turnpike indicated that excessively long and straight roadway systems led to driver fatigue. As a solution, Parkway planners and designers devised an alternative consisting of curvilinear alignments which were more organic in character and less monotonous in appearance. To minimize driver distractions and create variation in the landscape, opposing lanes of traffic were often separated by submerged medians containing stands of trees and/or artificial berms. The goal was to isolate the travel lanes from each other so that motorists would not be distracted by the oncoming headlights of drivers headed in the opposite direction. Hills provided an additional means of breaking up the monotony of long stretches of roadway in the southern sections.

The north- and southbound lanes of the GSP are separated by a median that ranges from 0 to 600 feet wide in some locations. In the northern metropolitan sections, the median is narrow and frequently nonexistent in order to allow the parkway to run through the more constrained urban areas. Some of these medians have been covered with grass, while more recently, others feature Jersey barriers which provide the sole means of separating the opposing lanes of traffic in these sections. In the southern rural sections, the roadways are often buffered from each other by grassy and tree-covered medians. These medians typically consist of narrow to wide swaths of land planted with grass and native shrubs and trees such as Ash, Beech, Linden, Red Oak, Weeping Willow, Azalea, Dogwood, Rhododendron, and Winterberry, among others. In some places, new trees were planted to replace those cleared for construction, while in others, the roadway traversed existing vegetation.

Detail of a narrow grassy median in the northern section, milepost and date unknown.

Detail of a Jersey barrier in the northern section, milepost and date unknown.

Detail of a grassy, sparsely landscaped median on an uneven terrain in the southern section, milepost and date unknown.

Overview of a wide, grassy, and landscaped median separating opposing lanes of traffic in the southern section, milepost and date unknown.

The north- and southbound lanes of the GSP are separated by a median that ranges from 0 to 600 feet wide in some locations. In the northern metropolitan sections, the median is narrow and frequently nonexistent in order to allow the parkway to run through the more constrained urban areas. Some of these medians have been covered with grass, while more recently, others feature Jersey barriers which provide the sole means of separating the opposing lanes of traffic in these sections. In the southern rural sections, the roadways are often buffered from each other by grassy and tree-covered medians. These medians typically consist of narrow to wide swaths of land planted with grass and native shrubs and trees such as Ash, Beech, Linden, Red Oak, Weeping Willow, Azalea, Dogwood, Rhododendron, and Winterberry, among others. In some places, new trees were planted to replace those cleared for construction, while in others, the roadway traversed existing vegetation.

Detail of a high wood-and-steel guiderail, milepost and date unknown.

Detail of a low wood-and-steel guiderail, milepost and date unknown.

High wood and steel guiderail under construction, milepost and date unknown.

Original guiderails and barriers were designed to adhere to a rustic aesthetic, and consisted of wooden beams attached to reinforced concrete posts. Modern safety standards have resulted in the replacement of most of these wooden guiderails with Core-Ten™ guiderails or concrete Jersey barriers.

The north and south bound lanes frequently diverged to avoid natural features and create visual interest as in this stretch near Cape May, 1956.

View showing the curvilinear design of the Parkway with its landscaped median to shield drivers from the distractions of oncoming traffic. Milepost and date unknown.

Parkway curves were often elevated, as seen in this photo of Exit 105 near Asbury Park, 1960.

Safety was among the most important considerations when the GSP was designed between 1952 and 1954. Most “modern” highways were perfectly parallel ribbons of asphalt and concrete with only a narrow patch of grass or concrete barriers separating opposing traffic lanes. “Not so with the Garden State Parkway. Wherever possible the opposite directional lanes take a course of their own-as though they were two different roads—and existing woodland or newly planted trees frequently make it impossible for a driver headed in one direction to see-and be distracted by-a car headed the other way.”

- Autobiography of a Parkway (1964)

Detail of Griffin's "singing shoulder," milepost and date unknown.

Narrow bands of textured concrete designed to vibrate and “sing” when a motorist ventured outside the travel lane lined the GSP. Former NJHA Chief Engineer Harold Griffin is credited with inventing this feature known as the “singing shoulder.” These concrete bands were also known as rumble strips.

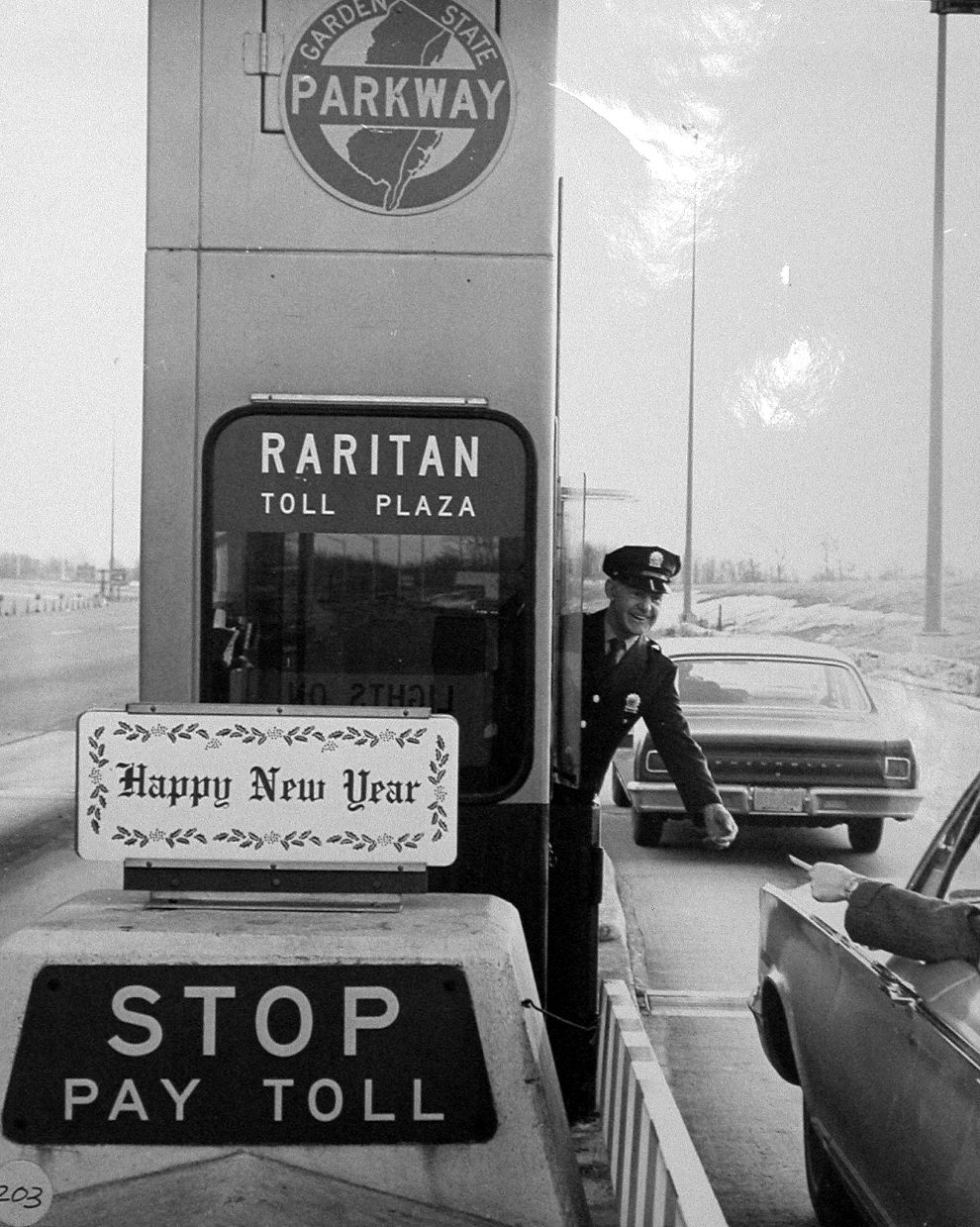

The GSP pioneered the use of full width toll plazas, such as the one shown here for Bergen plaza, 1963.

Most barrier toll plazas featured Colonial Revival administration buildings nearby, such as the one shown here for Egg Harbor Plaza. Date unknown.

Detail of an exit ramp toll plaza, location and date unknown.

The original toll plaza at Great Egg Harbor, 1955.

The GSP made use of two different types of toll plazas: barriers and exit ramps. The barrier plazas were designed to calm traffic by forcing motorists to slow down at specific intervals, and to compensate for the lost revenue from the toll-free sections in Essex, Union, Middlesex, Ocean, and Cape May counties. Originally there were attendants in each booth, though in 1955 the NJHA began testing automatic toll collection baskets. The baskets allowed motorists to toss exact change and proceed quickly without interacting with a toll collector. The exit ramp plazas allowed drivers to pay a lesser toll as they left the GSP than they would have if they were to continue on the Parkway.

The NJHA adopted the current logo in 1956.

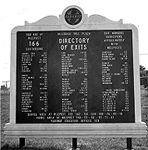

Rest Areas, service stations, and picnic areas each featured a directory of attractions and towns accessible via each exit.

Trapezoidal entrance signs, like the one shown here on the Atlantic City Expressway, distinguished the GSP from other highways of its time.

NJHA sign manufacturing facility. Date unknown.

The GSP was marked with hundreds of entrance, exit, directional, and informational signs along its 173-mile route. These signs were generally green and white and featured the GSP logo, adopted by the NJHA in 1956. Full service rest areas typically featured directories containing information pertaining to local attractions and towns organized by GSP exit number. The entrance signs were trapezoidal, designed to be different from those found on other highways at the time.

The 9-mile section of road that connected the GSP with the New York Thruway was completed in 1957. It was the last new section of the GSP constructed.

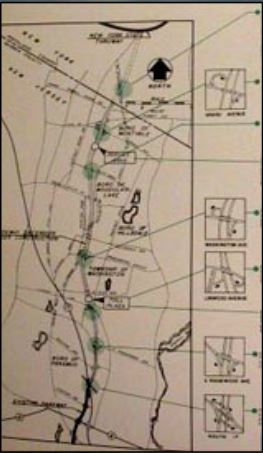

Overview showing the interrelationship between the GSP and various road crossings in the Metropolitan Section. Date unknown.

Overview showing the complex network of interchanges and road crossings along the GSP in the Metropolitan Section. Date unknown.

Although the GSP was planned and designed as one continuous alignment, it was developed for two very different types of motorists in two distinct communities. The section north of Asbury Park was regarded as the Metropolitan Section, designed to carry shoppers and commuters on short trips through and around the state’s most populated communities. Here the GSP resembled a modern superhighway more than a scenic country road as it passed through Newark, Union, and Woodbridge. In some places it divided communities in half, as entrance and exit ramps connected with local roads. The majority of the State Highway Department-funded sections were in this area and have remained toll free since their original construction.

Cape May terminus and intersection with U.S. Route 9, 1955.

The GSP separated the pine forests from the coastal marshes, as in Marmora, near Cape May, 1955..

More than 2,000 buildings were demolished to build the GSP, including these small tourist cabins along U.S. Route 9 in Cape May County.

The southern sections carved their way through the pine forests, crossed wide, slow moving rivers, and bypassed small crossroads communities on the way to Cape May. The Shore section was intended to carry motorists long distances to and from the beach towns, recreational areas, and state forests that dominated southern New Jersey. Where possible, the travel lanes were separated by wide tree covered medians and took advantage of scenic views and existing vegetation.

The GSP was also hailed as a necessary and effective firebreak in the pine forests.

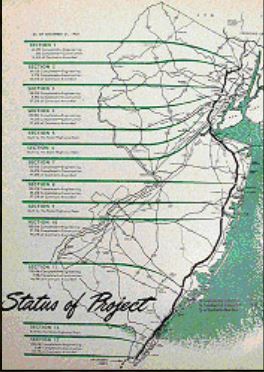

The NJHA published regular updates of their progress between 1952 and 1957, like this one from their 1953 Annual Report.

Gov. Robert Meyner, Commissioner Katharine White and a group of special guests cut the ribbon on the new York Thruway Connector in 1957.

Executive Director D. Louis Tonti and the Commissioners join a group of school children during construction near Newark.

Building a road as long and complex as the Garden State Parkway was nothing short of a Herculean task. Construction efforts began in 1946 when the State Highway Department began work on a 4-mile stretch in Bergen County. This section of the Route 4 Parkway, as the road was initially called, took nearly 4 years to complete, and was funded entirely through appropriations from the New Jersey Legislature. The Highway Department built two more sections, totaling 16 miles, around Paramus and Toms River between 1946 and 1953.

Frustrated by the slow pace and rising costs, Governor Alfred Driscoll convinced the New Jersey Legislature to create a special authority to oversee construction of the rest of the road and urged the voters to approve a bond referendum that would provide for all of the necessary financing in one lump sum. The New Jersey Highway Authority was created in April 1952 and in November of that same year, voters approved a $285 million bond referendum to pay for construction.

Construction began almost immediately and the entire 173-mile GSP was completed less than 5 years later. The New York Thruway Connector was the last major piece of new construction and was dedicated in July 1957. Construction of the 163-mile “main stem” between Paramus and Cape May took only 30 months from planning through acquisition and construction. The final cost of the completed GSP (not including the 20 miles paid for by the Highway Department) was $330 million.

NJHA Chief Engineer Harold Griffin and Design Engineer Oliver W. Deakin led a team of consultants including engineers, landscape architects, demolition contractors, bridge specialists, and paving contractors. Parsons, Brinkerhoff, Hall & McDonald, oversaw the entire project as the Consulting General Engineer with Clarke & Ramaupo and Coverdale & Colpitts serving as special consultants for landscape architecture and traffic engineering, respectively. The core design team was supported by a variety of local engineers working on specific sections of the GSP during various phases of design and construction.

There were an equal number of construction contractors performing a variety of tasks including demolition, grading, paving, building construction, and installation of lighting, landscaping, and guiderails. Geo. M. Brewster & Sons, Incorporated and S.J. Groves & Sons Company were awarded many of the early grading, paving, and drainage contracts. Other contractors included Poirier & McLane Corp, Union Building & Construction Corporation, Franklin Contracting Company, and Gerber Wrecking & Supply Company. Bethlehem Steel won the $4.8 million contract to install the superstructure of the Raritan River Bridge in 1953.

The Highway Authority relocated from Trenton to this historic farmouse near Red bank in 1954. The house served as the Authority headquarters until 1964 when a new facility was opened in Woodbridge.

The first car passed through the Bergen Toll Plaza on July 1, 1955.

A parade of antique cars participated in the dedication ceremony for the Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge in June 1956.

1946

November 8 - Gov. Walter Edge broke ground for the first section of the Route 4 Parkway at the Clark-Cranford-Winfield boundary.

1947

January - Alfred E. Driscoll, a Republican from Haddonfield, took office as the 43rd Governor of New Jersey. Driscoll served until 1953, and was largely responsible for enabling the construction of the Parkway.

1950

January 28 - Route 4 Parkway opened for travel between Route 27, Iselin and Central Avenue, Clark, in Union County.

1952

January 8 - Gov. Driscoll addresses the NJ Legislature and declared "There is an urgent need for additional parkways, freeways, and turnpikes to carry the commerce of our State and nation, to permit our citizens to travel more easily back and forth between their homes and businesses, for recreation, and, equally important, to achieve greater highway safety."

April 14 - Gov. Driscoll signed the New Jersey Highway Authority Act, authorizing construction of the Garden State Parkway.

July 2 - Gubenatorially appointed Commissioners Ransford J. Abbott, Bayard L. England, and Orrie de Nooyer took their oaths of office and held their first meeting.

August 7 - Temporary loans of $17 million were obtained from 138 New Jersey banks for initial planning and construction costs.

August 21 - The first two construction contracts were awarded by the NJHA.

November 4 - New Jersey voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot referendum to allow the Highway Authority to finance construction with $285 million in State backed bonds paid for over 35 years. The vote count was 908,142 for; 505,181 against.

1953

February - NJHA awarded a contract to the Cleveland Wrecking Co. in the amount of $124,474 for the demolition of buildings within the GSP right-of-way. A total of $125,204,391.30 was awarded in 1953 for construction on all sections of the Parkway.

May 25 - The New Jersey Supreme Court upheld a Superior Court ruling that the State guarantee of the bonds was constitutional. A taxpayer filed a lawsuit against the Highway Authority in December 1952 challenging the legality of the bond arrangement (Behnke v. New Jersey Highway Authority, 13 N.J. 14).

July - A 4-mile stretch between Cranford and Route 22, Union, opened for travel. This was the last stretch of the GSP constructed using State Highway funds.

1954

January 12 - The first NJHA constructed section of the Parkway between the Union-Essex County line and Route 22 was opened for

toll-free travel.

January 15 - George Vraken of Linden paid the first toll at 8:00AM at the Union toll plaza.

July 15 - A 17-mile section between Toms River and Rt. 72 in Manahawkin opened for travel.

August 4 - completion of several major construction projects allowed for uninterrupted north and south-bound travel for 80 miles between Irvington and Route 72, Manahawkin. The Raritan River (Driscoll) Bridge was also put into service.

August 8 - The one-millionth toll paying vehicle passed through a toll plaza.

August 28 - Completion of the section between Manahawkin and Somers Point allowed for 113 miles of unbroken roadway.

September 18 - The southern terminus of the GSP at Cape May was opened.

October 23 - Grand Opening Celebration held at Telegraph Hill near Holmdel, Monmouth County. Governors Meyner and Driscoll presided over the ceremony, which was followed by a box lunch for more than 3,000 guests.

November 19 - First automatic toll collection equipment installed as a test at Union toll plaza.

November 29 - Authority offices moved from Trenton to Red Bank and Eatontown

December 8 - The Parkway reached Newark, New Jersey’s largest city.

1955

May 12 - The Cheesequake Service Area, the first full service restaurant-gasoline rest area on the GSP, opened.

October 28 - The northbound lanes around Cape May were opened for travel.

1956

February 1 - The Authority entered into an Agreement with the New York State Thruway Authority “for the prompt, coordinated

construction of connecting links.”

April 16 - The Authority adopted the current logo as its official trailblazer.

May 1 - Chairwoman Katharine White broke ground for the 9-mile New York Thruway connector between Paramus and the New York-New Jersey border.

May 26 - The Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge opened for travel. The bridge was the last major construction project along the main stem and fulfilled the Authority’s initial obligations to its bondholders.

June 16 - Governor Meyner rode on the running board of a Stanley Steamer as it crossed the Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge during the Dedication Ceremony.

August 1 - Howard Johnson opened the restaurant at the Brookdale Southbound Service Area.

November 1 - Walter Reade, Inc. assumed operations at the four southernmost Service Areas.

1957

July 3 - The New York Thruway Connector opened to traffic. The Thruway Connector was the last section of new construction on the GSP. Several widening and interchange improvement projects were undertaken in 1958 and 1959. Similar projects have been planned and/or completed since the day the Parkway opened to traffic.

The NJHA collected more than $70 million in toll revenue during its first five years of operation. The 1- day record was $108,640.77 collected on August 1, 1959. The plaza toll was $0.25 and the ramp toll was $0.10 during that time.

The Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge under construction in 1956.

Thousands of acres needed to be cleared to make room for the GSP alignment.

Construction of the Parkway was an enormous undertaking and utilized a massive amount of materials. The following statistics were report by the Highway Authority in 1959 after the final 153 miles were completed. To put them in perspective, we've included some modern references.

Statistics related to the first 153 miles (excluding early sections)

Construction Cost-$330,000,000.00

Property Acquisition-$49,000,000.00

Clearing-4,300 acres - Equal to 1/3 of Manhattan or 3251 football fields.

Demolition-2,125 buildings.

Earth excavation-53,250,000 cubic yards - Could fill 94 Atlantic City Convention Halls.

Surface pavement-7,7,00,000 square yards (bituminous) - Could pave ½ the City of Perth Amboy.

Structural concrete-632,000 cubic yards (cement) - 614,000 cy of sand replenished on Brigantine Island in 2000.

Drain pipe-1,260,000 lineal feet - Nearly twice the length of the entire Jersey Shore.

August 1 - Howard Johnson opened the restaurant at the Brookdale Southbound Service Area.

Reinforcing steel-25,665 tons - More than 200 times the amount of steel in the Statue of Liberty.

Structural steel-37,100 tons

Piling-1,202,000 lineal feet

Top soil-7,555,000 square yards

August 1 - Howard Johnson opened the restaurant at the Brookdale Southbound Service Area.

SOURCE: The First Five years 1959:5.

If construction had continued at its pre-1952 pace and funding level, the Garden State Parkway would have been completed in 1992.

All operational and maintenance expenses were paid for by toll revenues.

The State of New Jersey attempted to pay for construction of the Parkway through appropriations to the Department of Highways beginning in 1946. There was never enough money available to complete large sections of the road, and it was feared that the project would never be completed if it was entirely reliant on state funds. The New Jersey Highway Authority Act passed in 1952 allowed the Authority to float bonds to pay for road construction, with the projection that the Authority would support all of its operations and maintenance through toll revenue. Anxious to begin work, and confident that voters would approve the referendum, the Authority borrowed $17 million dollars from 138 New Jersey banks in Summer 1952 and began design and construction immediately.

New Jersey voters approved a referendum on November 4, 1952 that allowed the Authority to float $285 million dollars in bonds with the backing of the State. Construction and debt service costs rose steadily throughout the course of the project and floated an additional $20 million bond in 1954. A third bond in the amount of $15 million was offered on January 1, 1956.

Toll revenue exceeded the projections offered by Coverdale & Colpitts within one year of the full Parkway's completion. In 1959, toll revenues were 10% greater than projected and the reserves were invested to finance future operational expenses.

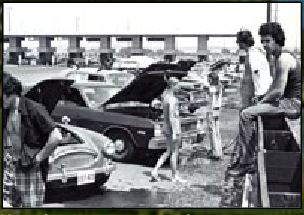

Motorists attempt to cool themselves and their cars near a toll plaza in 1971.

The GSP was a busy thoroughfare from the day it opened. This scene is in Wall Township on the first day of the GSP’s operation in 1954.

The NJHA published a series of maps highlighting a variety of recreational and historic attractions along the GSP that would be easily accessible to its motorists.

The Garden State Parkway was intended to be more than just a road; it was to be an experience. The curves, the scenery, the service areas, the toll plazas—all were designed to make driving the GSP safe and enjoyable. Unlike many roads built before and after it, the GSP blended speed with beauty. NJHA Executive Director D. Louis Tonti commented in 1964 that “the Parkway serves a dual function. For many it is, in a sense, a local road serving the commuter or the shopper. But for others, it is just part of a much longer trip. We have always tried to plan for the interests of both.”

The real benefit of the GSP was the time and money it saved drivers. The NJHA estimated that the average driver saved nearly 1.5 hours by driving the GSP instead of local roads on the 156-mile trip between Paterson and Cape May. Along the way motorists could enjoy a meal or service their vehicle at one of 8 rest areas, have a picnic lunch, or visit one of the many cultural attractions along the way.

Commuters could purchase rolls of GSP token to make frequent trips easier. While tokens are still accepted at toll plazas, they are no longer sold and are being phased out.

Automatic collector bins were installed in certain plazas in 1954. They became permanent fixtures at all tollbooths in 1955

Donna Celfo was one of the first female toll collectors hired by the NJHA. Celfo and several other women began work in 1975.

The Parkway, which opened to traffic in 1954, passes through 50 municipalities in 10 counties between the Cape May-Lewes Ferry in Cape May and the New York State line at Montvale. The highway is still at its original four lanes south of milepost 40 in Atlantic County and north of milepost 168 in Bergen County, but it has grown much wider in between. It’s now 12 lanes at its widest point in Monmouth and Middlesex counties. The highway is still at its original four lanes south of milepost 40 in Atlantic County and north of milepost 168 in Bergen County, but it has grown much wider in between. It’s now 12 lanes at its widest point in Monmouth and Middlesex counties.

The Parkway, which opened to traffic in 1954, passes through 50 municipalities in 10 counties between the Cape May-Lewes Ferry in Cape May and the New York State line at Montvale. The highway is still at its original four lanes south of milepost 40 in Atlantic County and north of milepost 168 in Bergen County, but it has grown much wider in between. It’s now 12 lanes at its widest point in Monmouth and Middlesex counties. The highway is still at its original four lanes south of milepost 40 in Atlantic County and north of milepost 168 in Bergen County, but it has grown much wider in between. It’s now 12 lanes at its widest point in Monmouth and Middlesex counties.

Walter Reade, Incorporated managed several rest area restaurants along the GSP, including "The Bibbery," a children’s diner at Forked River Rest Area in which adults could only be admitted when accompanied by a child.

There were 8 full-service rest areas along the GSP, offering food, restrooms, and gasoline.

The wide medians enabled rest areas to be located between north- and southbound travel lanes while also facilitating easy on and off access to the GSP

Drivers on the GSP were well provided for, and had access to numerous rest areas, picnic groves, and gas stations along the 173-mile route. Full-service rest areas in the medians offered sit-down restaurants, fuel, pay telephones, and bathroom facilities. In addition there were 5 gas-only stations in the congested northern portion of the GSP. There were also 8 picnic areas between Middlesex and Cape May counties where motorists could enjoy a snack or a meal amongst the Pinelands of South Jersey.

This rendering from 1953 shows the “New Jersey Colonial” style rest areas along the GSP.

The interior of a Howard Johnson restaurant during the early 1960s.

Howard Johnson, Incorporated was responsible for managing the GSP Information Center at the Cheesequake Service Area.

A sign directing motorists to the Polhemus Creek Picnic Area on the northbound lanes at MP 87.

The NJHA constructed 8 full-service rest areas along the 173-mile route, each with a restaurant and gas station. The wide medians in the southern sections allowed six of the service areas to be located between the opposing travel lanes and offer access to motorists traveling in both directions; Only northbound travelers could access the Vauxhall Rest Area at MP 141. The two remaining stations were placed on opposite sides of the GSP at MP 153 in Brookdale.

Each of the service areas centered on a one-story brick building built in the “New Jersey Colonial” style and reflected the growing national interest in Colonial Revival architecture. Inside was a full-service sit down restaurant operated by a contract vendor, with a portion of the gross receipts going back to the NJHA. Howard Johnson, Incorporated originally operated seven of the restaurants, but Walter Reade, Incorporated assumed management of the four southernmost stations in November 1956. Holiday House took over operations from Walter Reade in 1959. Holiday operated the Montvale station from the time of its opening in August 1958.

The gas stations at each of the rest areas were managed by one of four different fuel vendors. Texaco, Esso, Atlantic, and Cities Service shared management of the gas stations at the full-service rest areas.

In addition to the restaurants there were nine picnic areas between Tall Oaks (MP 137) and Stafford Forge (MP 61). The shady, wooded areas had picnic tables, grills, rustic bathroom facilities, and running water.

The fueling area at one of 8 full service rest areas along the GSP.

A Texaco station along the northern section of the GSP.

Esso gasoline was available at two of the Service Areas.

Gasoline was available at all 8 full-service rest areas along the main stem and at 5 fuel-only facilities in Middlesex and Union counties. The rest area stations were owned by the NJHA and operated under contract by the fuel companies. Initially four brands of gasoline, Cities Service, Esso, Texaco, and Atlantic, were available. Cities Service operated four of the nine stations. The standalone facilities were privately owned and operated, and were constructed in pairs on opposite sides of the GSP.

The 300-year old Shoemaker Holly near Cape May, celebrated as one of the oldest trees in New Jersey, was spared from demolition and became the centerpiece of the Shoemaker Holly Picnic Area.

The GSP was at its root, a means to achieving an end. For millions of people of New Jerseyans and East Coast residents, it was the way to the Shore and the dozens of other recreational and historical attractions New Jersey had to offer. The GSP’s proximity to the coast made it the route of choice for people traveling southbound from the urban areas of New Brunswick, Newark, Union, and Manhattan to Atlantic City, the Wildwoods, and Cape May. The NJHA viewed the GSP not just as a road, but as a vital economic development tool and took every opportunity to promote the diverse places to go and things to do along the GSP’s 173-mile corridor.

Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Lucy, the Margate Elephant. Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Perhaps the single most important reason for building the GSP was to provide access to the numerous resort communities along the New Jersey Shore. Atlantic City, the Wildwoods, and Cape May were long established beach towns with a booming tourism industry. The problem was getting there. The trip from northern New Jersey could take upwards of 5 hours prior to the GSP’s construction, meaning that only people of means could afford to take the time off work to make the trip worthwhile. The GSP helped make the Jersey Shore accessible to anyone with a car.

The GSP enabled working- and middle-class families an easier means of access to the Shore which in turn spurred a wave of new development and economic activity there. Long established communities such as Atlantic City and Cape May experienced new interest, while other communities such as Wildwood began to flourish as a result of widespread motel development catering to families. Employing design themes ranging from Polynesian to Space Age, Wildwood emerged as a Mid-20th- Century Modern resort area in its own right. Other towns, such as Seaside Heights and Barnegat, also prospered by welcoming working class vacationers, while Ocean Beach became the shore equivalent to New York’s Levittown and New Jersey’s Willingboro, boasting row upon row of affordably priced cottages.

Upper-middle-class beachcombers continued to vacation at the Shore, but instead of gravitating to Atlantic City, Wildwood, and Barnegat, began frequenting the more upscale communities of Stone Harbor, Beach Haven, or Bay Head.

Sign for the Cape May-Lewes Ferry. Date unknown.

The GSP began at Milepost 0 in Cape May, just 3 miles from the coast and 17 miles from Lewes, Delaware. The Highway Authority Act passed in 1952 authorized the Authority to develop and operate a passenger ferry between the two points, but the effort failed because Delaware did not have companion legislation that authorized the ferry’s operation on its side of the Delaware Bay. Several efforts initiated by the NJHA stalled and ultimately failed throughout the 1950s, and it was not until the creation of the Delaware River Bay Authority (DRBA) in 1962 that the project was given any chance of true success. In 1964 DRBA began operation of the Cape May-Lewes Ferry.

The circular amphitheater was the centerpiece of Stone’s design for the Garden State Arts Center.

The amphitheater under construction, 1967.

Liberace signs autographs following a special performance at the Garden State Arts Center. Date unknown.Project 2

The 400-acre Telegraph Hill Nature Area prior to construction of the Garden State Arts Center.

In addition to building and managing the Garden State Parkway, the NJHA was also responsible for developing roadside attractions and recreational facilities. The Authority purchased the 400-acre Telegraph Hill Nature Area in Holmdel, Monmouth County during the initial right-of-way acquisition for the GSP. The large park at Exit 116 included trails, picnic areas, and observation points and became the home to one of New Jersey’s premiere performing arts venues.

American architect Edward Durell Stone (1902-1978) designed the 5,300-seat Garden State Arts Center in 1965 and ground was broken in May of the following year. Stone had collaborated on designs for Radio City Music Hall and the original Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and was the principal architect for the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. and the US Embassy in New Delhi, among others.

The Center opened for performances on June 12, 1968. The large, circular stage house was situated atop a hill overlooking the GSP. The gently sloping lawn surrounding the amphitheater provided outdoor seating for an additional 5,500 people.

In addition to hosting musicals and stage performances, the Arts Center has become home to numerous ethnic heritage festivals sponsored by the Garden State Arts Foundation. In May 1995, the State of New Jersey and the NJHA dedicated the New Jersey Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial on the grounds of the Arts Center. In 1996, the Garden State Arts Center was renamed the PNC Bank Arts Center.

The Troop E Headquarters, New Jersey State Police in Holmdel, 1955.

A telephone booth along the GSP, date and milepost unknown.

Katharine E. White, NJHA Chairwoman from 1955-1964, served as a member of the President’s Committee on Traffic Safety in 1962.

Safety was one of the most important considerations in both the design and management of the GSP. The divergent roadways, tree-covered medians, and singing shoulders helped to keep drivers focused on the road and not become distracted by oncoming vehicles. The GSP boasted of its safety record and in 1963 the National Safety Council and the American Bridge, Tunnel, and Turnpike Association declared it to be the “safest superhighway in the nation.” The GSP averaged 0.7 fatalities per 100 million miles of travel in 1963. The national average for all roads that year was 5.4 and 2.4 for all turnpikes.

The New Jersey State Police created a special unit, Troop E, to patrol the entire length of the GSP. A new headquarters designed in the signature Colonial Revival style was built near Holmdel and served as the Troop’s base of operations.

Telephone booths and emergency call boxes lined the GSP at regular intervals to allow motorists to contact the State Police or other emergency services if necessary.

The Garden State Parkway was featured prominently in the New Jersey Pavilion at the 1964 World's Fair in New York.

Miss Parkway Beauty Contest, c.1965.

Exhibit touting the Garden State Parkway. Location and date unknown.

The NJHA worked hard to convince New Jersey residents that their tax monies and tolls paid for the initial construction and maintenance of the GSP were both sound investments. The NJHA maintained an active public relations department that fielded inquiries, developed exhibits, and sponsored contests to promote the GSP to New Jerseyans and to the rest of the country. Exhibits espousing the benefits of the GSP and the opportunities it provided were set up at trade shows, rest areas, and visitors centers across the state. The GSP was featured prominently in the New Jersey Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. The Miss Parkway Contest ran for a number of years in the early 1960s, and dozens of young women competed for the right to wear the crown.

The NJHA produced modest maps such as this one in its annual reports to identify historic towns along the GSP‘s route. These maps were accompanied by text highlighting each town’s historic significance.

View of the southern section, location and date unknown.

The role that the GSP has played in the history of New Jersey is significant and immeasurable. It was at once, both an economic development tool and a wonder of modern design. The GSP has been recognized as a historically significant resource by the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office and is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

To celebrate the many births that occurred along the GSP, the NJHA established “The Stork Club” and hosted annual birthday parties for the children. In 1964, there were 23 members of the Club.

The GSP incorporated many modern traffic control and safety features into a scenic, landscaped setting.

With its emphasis on the natural landscape, the GSP distinguished itself from other expressways, such as the Pennsylvania Turnpike as shown above.

The Garden State Parkway changed the way New Jerseyans lived, worked, and played. The entire GSP, from Milepost 0 in Cape May to the New York State line, has been determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places by the New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office. The GSP is historically significant for its role in the development of the Jersey Shore. In addition, it is architecturally significant as a “well-defined example of the evolution of parkway design that by the 1950s blended the original 1920s/30s concept with the needs of the modern superhighway.”

The physical elements that define the GSP and represent its historical significance include: bridges and culverts, retaining walls, grassy medians, controlled access with non-signalized interchanges, an absence of advertising, standardized signage, concrete and wooden guiderails, picnic areas, toll plazas and administration facilities, State Police barracks and maintenance areas, gentle grade, super-elevated horizontal curves, earthen berms, wide shoulders, limited curbing, its dull sage green color scheme, pullovers with telephone booths, acceleration lanes, and the incorporation of native vegetation.

The GSP ushered in a new wave of development along the Jersey Shore, contributing to the growth of the tourism industry, residential development, and overall economic growth in this region. In fact, the GSP was seen as integral to the state’s economic growth in the wake of World War II, and was developed during a time when public funds were depleted from World War II and bond-financed toll roads were the fastest and easiest form of transportation projects.

The GSP is also significant as an example of an innovative highway design that combines the bucolic attributes of earlier parkways, such as the Bronx River and Merritt parkways, with the speed and safety of a modern superhighway.

By 1964, motorists had traveled more than 11 billion highway miles on the GSP, enough mileage to equal almost 50,000 trips to the moon.

The GSP was promoted as a necessary route for advancing tourism, recreation, and quality of life. This collage was featured in the NJHA Annual Report in 1953.

The NJHA anticipated that residential and commercial growth would be among some of the benefits accrued by the introduction of the GSP.

“In the days immediately following World War II, everybody knew New Jersey needed a new super highway- a north-south artery through which the State’s economic pulse could surge. Every motorist who had ever been helplessly snarled in a weekend traffic jam on his way to the Jersey shore knew it; Every industrialist and banker and economist who realized the vast potential of the State’s largely undeveloped southland knew it; But if everybody knew that New Jersey needed this road, nobody seemed to know how to get it.”

- New York Times, August 2, 1964

The Garden State Parkway was planned to help generate economic activity and revitalize the state’s sagging tourism industry. Many of the Shore communities suffered through World War II, as men were shipped off to war and women ventured in the work force. Vacations were not part of the daily lives of most Americans. The decline in tourism dollars was noticeable and the shore communities suffered a particularly hard year in 1948. GSP supporters hoped to reverse that trend by making it faster, cheaper, and easier for people in northern New Jersey and New York to reach places like Atlantic City and Cape May.

The GSP exceeded the expectations placed upon it by political leaders and the general public. The numerous interchanges were quickly surrounded by housing developments and shopping centers. In the first year alone, the ten counties that the GSP passed through gained $300 million in tax ratables, owing to new construction and resident and tourism dollars. In 1958, those same ten counties earned $269 million in ratables, four times the amount earned in New Jersey’s other eleven counties. These ratables were not just driven by tourism, though. Ocean County’s permanent population increased five-fold between 1950 and 1976.

Atlantic City Electric

New Jersey Turnpike Authority

NJDEP-Historic Preservation Office

Cultural Resource Consulting Group

The New Jersey Turnpike Authority (NJTA) was created by an Act of the New Jersey State Legislature in 1948 for the purpose of constructing, maintaining, repairing, and operating the New Jersey Turnpike. In May 2003, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority Act was amended to consolidate the management and operation of both the New Jersey Turnpike and the Garden State Parkway under the control of the NJTA.

This website was originally designed and developed by Atlantic City Electric, a subsidiary of Pepco Holdings, Inc., providing safe and reliable electric service to more than 500,000 customers in southern New Jersey. The website is now run by New Jersey Turnpike Authority.

Most of the images that appear on this website are from the New Jersey Highway Authority Archives (now housed at the New Jersey Turnpike Authority (NJTA) Headquarters, Woodbridge, NJ) and are used with the permission of the NJTA, unless otherwise noted. The text of this website was written by Cory Kegerise and Gregory Dietrich of Cultural Resource Consulting Group (CRCG) in consultation with Atlantic City Electric, the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office, and the NJTA.

All information presented on this site has been taken from a variety of primary and secondary source material, including:

·Annual Reports of the New Jersey Highway Authority, 1952-1956.

·“The First Five Years of the Garden State Parkway.” New Jersey Highway Authority, 1959.

·“Autobiography of a Parkway”, New York Times Special Advertising Section, August 2, 1964. ·Various histories of the GSP developed by the New Jersey Highway Authority. ·Technical Memorandum No. 18 Cultural Resources Investigation Widening of the Garden State Parkway Interchange 30 to Interchange 80. Prepared by Richard Grubb & Associates for T&M Associates, 2000. ·Archaeological Survey for the Widening of the Garden State Parkway, Milepost 30 to Milepost 80, Atlantic, Burlington, and Ocean Counties, New Jersey. Prepared by Gannett Fleming, 2002.

The content of this website has been reviewed and approved by the NJTA. The purpose of this site is to provide historical information relating to the development of the GSP and not to provide information about actual travel conditions, tolls, or other such information related to the GSP’s ongoing use.

CRCG would like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their support and assistance in producing this website:

Dana Small and Robert Jubic, Pepco Holdings, Inc. Denise Rees, Shawn Taylor, Mary Kay Murphy, and Bruce Conner, NJTA Andrea Tingey, New Jersey Historic Preservation Office Caleb Kercheval and Mike Goodsell, Hamptons Online.